Two moorish women playing chess to lute music. From a chess book in the great library in El Escorial, written in 1283. The fascination that chess holds for so many people is not difficult to understand even for non-players: Two players locked in mortal combat, each in control of an army, with the single objective of destroying the enemy king! Each player totally dependent on his own skill, imagination, resourcefulness, judgment; with no place for sheer luck! No wonder so many chess terms have found their way into everyday language!

Of course, different players savor different aspects of the game. Some people relish the duelling aspect, the battle for supremacy, dominating your opponent. - When asked what he liked about chess, Bobby Fischer, the erratic world champion of the 1970s, is said to have replied: "I like to see them squirm." - An earlier world champion, Emanuel Lasker, was famous for playing his opponent as much as the position. - Other players enjoy unraveling the mysteries of a position and view the game as a joint search for the truth, in partnership with the opponent. Some even consider chess to be an art form.

No doubt, many players enjoy the game simply because they have discovered that they have a talent for it. In chess, they may enjoy some status and prestige that might be denied to them elsewhere.

And competitive people, just as in other sports, such as golf, may like the objective ranking system which lets them know exactly where they rank on the "totem pole", and which allows them to measure their progress quantitatively.

Very young children have their own reasons for appreciating the game. Just leave the board and men within striking distance of a five-year old, and you will see what I mean. The visual and tactile attraction is irresistible to them!

But its fascination is not really what I find surprising about chess. What seems amazing to me is the richness and depth of the game, and the enormous room that it leaves for players of all strengths, from beginner to world champion. How can there be so many steps on the ladder? After all, the inventor(s) of chess cannot possibly have had more than a very shallow understanding of the game. If he returned today, he would find himself completely outclassed.

In fact, the rules changed (slow load from archive) a lot during medieval times. The game is thought to have had its roots in India not later than the 7th century, perhaps a lot earlier. It spread to Persia and Arabia, from where it entered Europe via several routes (Russia, the Byzantine empire, Italy, Spain). - The Swedish 19th century bishop and poet Esaias Tegnér appears to have been justified in imagining a chess game between Vikings. "Every second square made of silver, every second made of gold..." - At that time the queen (originally the vizir, the king's adviser) was a much weaker piece, only allowed to move one square diagonally at a time. The bishop (originally the elephant) was also weak; it could only move two squares at a time diagonally (but jump over a friendly piece). Pawn promotion meant promoting to the piece corresponding to the file where the promotion took place (so that e. g. a pawn on the b file was promoted into a knight).

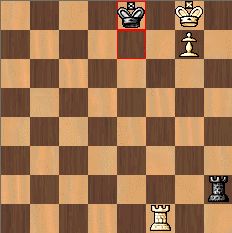

Smothered mate from one of my "bullet" games on the Internet (60 sec + 1 extra sec per move). White mates in 5.

Solution here.By the 15th century, the rules had been modified substantially and had, in essence, become our modern ones, although the rules for castling were not universally agreed until the 18th century. - Yet, when my grandfather taught me to play chess in the 1940s, he told me that pawns promoted into pieces corresponding to the file of promotion, and that instead of moving a pawn two squares from the second row, you could elect to move two pawns one square each. How could those vestiges of medieval rules have survived for 500 years?? Perhaps he just made rules up that seemed reasonable to him?

Thus, the modern rules of chess are less than 500 years old, and were the result of considerable experimentation, so they probably were not "invented" by some unknown genius in isolation.

In time, an extensive chess literature emerged. The Arabs, in particular, published problems and endgame puzzles, "mansubas" (slow load from archive). The Spanish player Lucena wrote a treatise on the game in 1497. Some of his discoveries form part of the tournament player's standard arsenal today, for instance how to win "Lucena's position" and how to force a "smothered mate". Still, even the founding fathers of modern chess five centuries ago cannot possibly have foreseen how much room there would still be for improvement in the quality of master games under the agreed rules.

And progress was slow for several centuries. Not until Philidor in the 18th century was there a clear step forward in understanding, and only in the mid-19th century, players such as Anderssen, Morphy and Steinitz raised the standard of the game to a new level. Since then, there has been steady progress at the top level. - How can we know? Largely by subjecting the games of earlier generations to computer analysis. Today the best computer programs have just surpassed human world champion strength!

Computers are also the main reason why rapid progress is still possible at champion level. They form an invaluable tool for analysis and training.

The Elo rating system

Nowadays, the strength of chess players is measured by a rating system originally devised by Arpad Elo, a Hungarian-born statistician. Players are rated roughly between 1000 and 2800 on the Elo scale. Complete beginners are usually entered somewhere at 800 or 1000 (not at 0, as they might then quickly wind up with a negative Elo rating!). Most club players are to be found in the interval 1200-1900. The bell curve peaks at around 1600 or so (although it is not really a bell-shaped distribution, se below). Expert and master players can be found above 2000. Players with the titles of International Master (IM) and Grand Master (GM) will typically have Elo scores in the range 2300-2600. Above 2600, you will find the players informally known as Super GMs. The World Champion has a rating approaching 2800.

In a match between two players of equal strength, the outcome should on average be even. If equally rated players play a tournament game, the winner gains 16 Elo points, and the loser loses 16 points. A draw will not cause a transfer of Elo points. But if there is a large difference in Elo rating, say 200 points, the winner gains many more points from his opponent if he is the lower-ranked player than if he is the higher-ranked player (and therefore expected to win). Even a draw will cost the higher-ranked player rating points and gain points for the lower-ranked player.

Note added in March 2024:

Recently, the rating system has been revised by the International Chess Federation (FIDE) to address creeping rate deflation. This is caused by the influx of large numbers of rapidly developing young players, whose ratings tend to lag their true strength. The entry point has been raised to 1400 points, while ratings above 2000 have been left unchanged. This will reduce the risk of strong players unfairly losing rating points when facing low-rated players. - This may seem as a rather arbitrary rule modification, but it is based on a detailed and well-researched investigation by Jeff Sonas that makes for fascinating reading, at least for a mathematically inclined chess player. - In passing, we learn that chess players on average now reach their peak at the age of 29. Seems like yesterday!But back to the subject of "the many steps on the ladder" of chess performance. The thing that I find so surprising is that there is so much room for improvement even after you have reached the Expert level. A player rated, say, 200 Elo points higher than his opponent is clearly a stronger player. But from my own approximate level of 1800, there are at least five such distinct steps to the world championship level. - This reminds me of Kafka's famous parable about the series of gatekeepers guarding the entrance to "The Law": "But from hall to hall there are doorkeepers, each one more powerful than the last. Not even I can stand to look at the third one."

On the Internet Chess Club (ICC), most games are "blitz" or "bullet". ICC uses an Elo-type rating system for these categories. In blitz play (typically 5 minutes per player for the entire game), the very best players may reach a rating of 3500. - After having played 14,000 blitz games on ICC Internet over the past 7-8 years, it is clear that my ranking will never climb much higher than 1900 or thereabouts. Compare this to the Norwegian "wunderkind" Magnus Olsen, who achieved a blitz ranking on ICC of 3332 when he was just 13 years old!!

It has often been pointed out, that chess, along with music and mathematics, offers great opportunities for child prodigies. Here a youngster can sometimes display amazing powers. This is much less common in fields where more experience or maturity is needed, such as literature or painting.

It is a matter of debate whether a talent for chess is inborn or can be developed through rigorous training during childhood and adolescence. "Nature or nurture?" - A famous experiment was carried out by a Hungarian teacher, Laszlo Polgar, who claimed that "geniuses are made, not born". To prove his claim, he systematically trained his three daughters in chess from a very early age. All three of them became champions! The most successful of them, Judith Polgar, is one of the 20 best players in the world, a "super GM". But most likely, such training must start at a very early age to have the desired effect.

As a young teenager I visited that mecca of Stockholm chess, "Schacksalongerna", Drottninggatan 29C, in the central city. I was hugely impressed to watch players playing blitz games using just one or two seconds per move. How was that possible? To a non-player, it may seem impressive that anybody can calculate chess positions many moves ahead, and incredible that strong players can play blindfolded - and play well. (In fact, GMs have on occasion been known to play 40 or 50 blindfold games simultaneously against amateurs, winning almost all of them.)

What impresses me even more - now that I am myself capable of playing blitz (and "bullet"!) games reasonably well - is that the goal of becoming a really strong player seems just as far off as when I was a beginner, even - let us face it! - out of reach forever. The end of the rainbow keeps receding as we approach it.

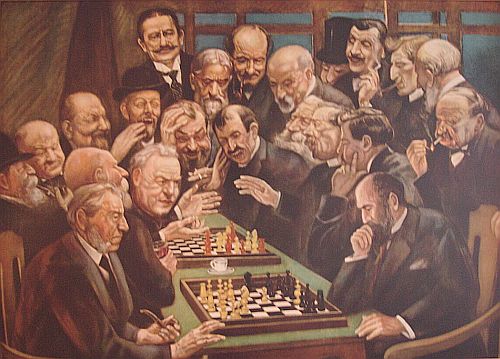

A photo of a copy at Täby Chess Club of a section of a painting at Schacksalongerna by the Finnish-Swedish artist Annti Favén. Several strong players of the early 20th century are portrayed: Tarrasch, Marshall, Janowsky, Burn, Bernstein.

No.

of

play-

ers

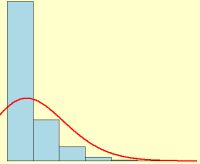

To understand the reason for this, consider this diagram (not based on actual data). There are many more weak players than players of intermediate strength, and many more intermediate players than strong ones. But what many people fail to realize, is that the graph continues very far to the right. There are not many players that strong, but among them the difference between a super GM and a mere expert is just as big as the difference between a strong club player and a beginner.

Or put in different terms: while we might think that chess ability should be distributed symmetrically around an "average player", which would give a symmetrical "bell curve", the distribution is actually much more similar to a Poisson distribution, familiar to statisticians, and sometimes known as "The Law of Rare Events".

Speaking of rare events, it should be a great comfort to all of us "patzers" that the present world champion, Vladimir Kramnik, a demi-god in the chess world whom I have just declared to be as far ahead of me as I am compared to a mollusk, recently overlooked a mate in one! True, this occurred in an exhibition match against a computer, but the stakes were high, both in terms of money and prestige, and he was not under time pressure. Quandoque bonus dormitat Homerus!