|

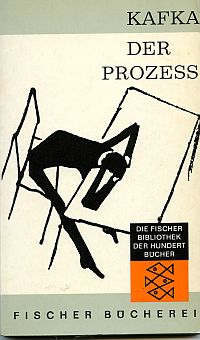

Der Prozess

(The Trial) - Franz Kafka

|

||||

The very name Kafka brings to mind images of bottomless despair. There are even T-shirts with the legend "Kafka didn't have much fun either". And it is true that he had a difficult life, which is reflected in his novels and diaries. For instance, there is the story about how "Gregor Samsa" woke up one morning to find himself turned into a beetle. Yet it is not the whole picture. Many of his works are filled with a wonderful humor. - Once when my mother was riding the subway to work, she shook uncontrollably with laughter as she was reading Das Schloss (The Castle), much to the puzzlement of those passengers who could see what she was reading. Probably his best-known work is "The Trial" (the German original is here). Just as the first few bars of Wagner's "Tristan and Isolde" set the mood for the whole opera, "The Trial" starts with this gripping sentence: "Someone must have been telling lies about Josef K., for without him having done anything bad, one morning he was arrested." I found myself spellbound when I first read this opening in my twenties. Today, forty years on, it triggers even stronger emotions. The rest of the novel describes Josef K.'s efforts to clear himself of the false accusations. In the process of doing so he encounters a never-ending series of obstacles. The mindless judicial system forces him to work his way through a labyrinth of appeals, uninterested civil servants (including his defense lawyer), and dusty documents. His struggle is summed up in a parable near the end : "You are very friendly to me," said K. [to the prison chaplain]. "You are an exception among all those who belong to the Court. I have more trust in you than in any of the others I know. I can speak openly with you." "Don't delude yourself," said the chaplain. "How would I be deluding myself?" asked K. "You delude yourself in the Court," said the chaplain, "in the opening paragraphs to the Law, it says about this delusion: In front of the Law there is a doorkeeper. A man from the countryside comes to this doorkeeper and asks to be admitted to the Law. But the doorkeeper says that he cannot let him in now. The man ponders this, and then asks if he will thus be permitted to enter later. 'Possibly', says the doorkeeper, 'but not now'. As the door to the Law is open, as always, and the doorkeeper has stepped to one side, the man stoops to try to peer in. When the doorkeeper notices this he laughs and says, 'If you find it so tempting, just try to enter even though I will not allow it. But note: I am powerful. And I am only the lowest of all the doormen. But from hall to hall there are doorkeepers, each one more powerful than the last. Not even I can stand to look at the third one.' The man from the country had not expected such difficulties, the Law should be accessible to anyone anytime, he thinks, but as he now looks more closely at the doorkeeper in his fur coat, sees his big pointed nose, the long, thin, black Tartar beard, he decides to wait until he gets permission to enter. The doorkeeper gives him a stool and lets him sit down by the door. There he sits for days and years. He makes many attempts to be let in and tires the doorkeeper with his pleas. From time to time the doorkeeper interrogates him, asking where he comes from and many other things, but these are disinterested questions such as great men ask, and he always ends up telling him that he still cannot let him in. The man, who had come well equipped for his journey, uses everything, however valuable, to bribe the doorkeeper. He accepts everything, but as he does so he says, 'I am only accepting this so that you will not think that there is anything you have neglected to do'. Throughout the many years, the man watches the doorkeeper almost without interruption. He forgets about the other doormen, and it seems to him that this first one is the only obstacle to gaining access to the Law. Over the first years he curses his misfortune loudly, but later, as he becomes old, he just grumbles to himself. He becomes infantile, and as over the years of study of the doorkeeper, he also has come to know the fleas in the doorkeeper's fur collar, he even asks them to help him and to change the doorkeeper's mind. Finally his eyes grow dim, and he no longer knows whether it is really getting darker or just his eyes that are deceiving him. But in the darkness he now discerns an inextinguishable brightness emerging from the darkness behind the door. He does not have long to live now. Just before he dies, he collects all his experiences from all this time into one question which he has still never put to the doorkeeper. He beckons to him, as he is no longer able to raise his stiff body. The doorkeeper has to bend over deeply, as the difference in their sizes has changed very much to the disadvantage of the man. 'What is it you still want to know?' asks the doorkeeper, 'you are insatiable.' 'Everyone strives to reach the Law,' says the man, 'why is it that, over all these years, no one but me has asked to be let in?' The doorkeeper sees that the man has reached his end, and to overcome his fading hearing, he shouts to him: 'Nobody else could have gained admission here, as this entrance was meant only for you. Now I will go and close it'."

The text then goes on to dissect this parable, in a dialog between Josef K. and the chaplain, much as, I imagine, Talmud scholars would analyze a "holy writ". What is it that makes this little story so fascinating? Well, first there is its dreamlike, almost hypnotic, quality. Then there is the enigma it raises. The most obvious interpretation is that it describes a search for God or despair at His absence in a cold and uncaring world, but it could equally well be read as an allegory over unrequited parental or romantic love. Many read "The Trial" as a premonition of nazism and the holocaust, but surely there was enough anguish in Kafka's environment to explain his "angst", without turning his work into a prophecy. There was his Jewish background in a Prague filled with ethnic animosities, there was the horror of World War I with its senseless butchering of millions of young men. "The Trial" was written in 1914-15. I am sure that the dying days of the Austrian Empire were very different from the idyll of the Strauss waltzes. ("Austria's genius was to make the world believe that Beethoven was Austrian, and Hitler was German.") After the war ended, the Spanish flu claimed many victims among those weakened by war rations and the Allied hunger blockade. The byzantine bureaucracy fostered by the Austrian Empire probably formed part of the inspiration for "The Trial", "The Castle" and other works. By the way, it is an amazing fact that the Emperor Franz Josef had reigned for 68 years when he died in 1916. When war broke out in 1914, his proclamation of war started "An meine Völker" (to my peoples). And "Der König von Italien hat mir den Krieg erklärt." (The king of Italy has declared war on me.) Kafka himself was a very sensitive person. His biographer and friend Max Brod describes how Kafka sometimes was in tears over some hard-luck story among his clients. He worked as an insurance claims agent during daytime, and labored with his writing at night. Sleep deprivation was a constant problem for him. Kafka ordered that all his manuscripts should be destroyed after his death. Fortunately, Max Brod, as custodian of his manuscripts, failed to obey his order. Today Kafka seems to have become more of an icon than a "must-read" author. This is unfortunate, for his stories are highly readable, and the world he describes is not that different from our own. |