|

The

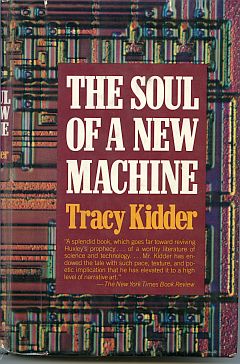

Soul of a New Machine - Tracy Kidder

|

|||||||

|

The author of The Soul of a New Machine worked as an "embedded reporter" in the team that developed Data General's first 32-bit computer back in 1979, the "Eagle". There was a lot of turbulence in the computer industry around that time. (This is always the case, thanks to Moore's Law.) Minicomputers were just starting to have an impact on IBM's dominance and business model. The industry was jokingly referred to as "IBM and the seven dwarfs". Until that time, computers were typically "mainframes" run by those large organizations that could afford them. They were usually controlled by a computer department, where users could submit "jobs" and receive the results in the form of printouts a few hours later. During the 1970s, access through remote terminals became popular, and I can remember how impressed I was when one of my colleagues at Swedish Space Corporation was able to edit programs and submit jobs to a computer in downtown Stockholm from the terminal in his office. A major upheaval occurred when Digital Equipment Corp. (DEC) launched its series of VAX 32-bit minicomputers in the late 1970s. Suddenly, smaller organizations and individual departments in larger companies could afford to acquire their own computers, and run them under their own control. In just a few years, the market for minicomputers exploded. - Data General was the second largest manufacturer of minicomputers, and its 16-bit minicomputers had been quite successful. However, the company had failed in its development of a 32-bit contender, had had quality problems and was facing massive defections of its customers to DEC. On top of this, there was internal rivalry between its development organizations in South Carolina and Massachusetts. The book tells the story of how the project manager, Tom West, managed to sell the company's founder Edson de Castro on the need to develop a 32-bit computer as a backup to the main effort underway in South Carolina. Approval was given under rigid restrictions. At the same time, he had to assemble a development team and convince its members that the work was technically pioneering and challenging at the highest level, despite the restrictions, and that it would reach the production stage if succcessful. West gathered a few seasoned veterans in his team, but most of the members were newly hired graduates straight out of college. It appears that this was a deliberate strategy to ensure enthusiasm and dedication to the project among team members in the face of an impossible deadline, meagre resources and technical restrictions imposed by top-level management. What followed was an intense effort in a pressure cooker environment filled with 80-hour work weeks. The book describes the inevitable crises that beset the project and how they were overcome. Ultimately, the project was crowned with success. It came at a cost: many members suffered from a disrupted social life and the phenomenon known as "burn-out" (which nowadays has become a catchphrase for all kinds of real and imagined ailments). But the book is above all a celebration of the passion that drives these young engineers.

Right at the end, there is a poignant epilogue: "At the end of the presentation for the sales personnel in New York, the regional sales manager got up and gave his troops a pep talk. - 'What motivates people?' he asked. He answered his own question, saying: 'Ego and the money to buy things that they and their families want.' It was a different game now. Clearly, the machine no longer belonged to its makers." The book is very well written, and it won a Pulitzer prize. Of course, there is a tendency to dramatize and simplify in order to make the book attractive to a wide audience, but nothing that "tends to belittle the complexity of our profession" - a phrase that has stuck in my mind from a review of a completely different book. Furthermore, Kidder does a commendable job of explaining technical issues to a lay audience. Re-reading the book today, 25 years after it was published, brings back fond memories of some episodes in my own professional life. One is the playfulness of the engineers. A rudimentary form of programming without access to a computer became available when the HP-67 scientific calculator was launched in 1976. A little later, microcomputers started to replace typewriters. They offered a platform for Basic programming and for simple text-oriented games such as Adventure. ("You are in a twisty maze of passages, all alike.") Later, when we got a VAX system, we used to play Snake in the evenings - a simple graphics game built on ASCII characters. When the Commodore-64 became available in 1982, I started programming and playing games at home for a while. What in particular brings me into resonance with the book, however, is two episodes, two comparatively short periods when I was involved in intense technical development at Swedish Space Corporation (SSC): the perfection of an Image Analysis System (IAS) delivered by MacDonald Dettwiler (MDA) in 1979, and the development within SSC of the EBBA image analysis system, hosted on microcomputers, which culminated in 1984-86. What is it that seems to make many scientists and engineers, in particular, so dedicated to their work? According to Gibran, work has a spiritual dimension. All work done with love is blessed. - And what is it to work with love?

This is a poetic and moving description of what many people experience, even when the work itself may be routine. But I think that it misses an essential part of what makes work enjoyable: "All work and no play makes for a very dull day", as the saying goes. Working with computers, and with advanced technology in general, has an element of playfulness in it that I think lies right at the core of what makes us human. Playfulness is an important characteristic of human culture, as the Dutch humanist and historian Huizinga argued in his book Homo Ludens (1938). This brings to mind a Swedish film, "De lyckliga ingenjörerna" ("The Happy Engineers"), which documented the development and successful launch in 1986 of our first satellite, Viking. The title can be interpreted as an expression of envy - or perhaps as reflecting a slightly condescending attitude to engineers, thought to be working in a certain isolation from "the real world". Which reminds me of this literary masterpiece by Hans Botwid:

I think we can assume that, just like so many engineers, Jonson has managed to turn his hobby into his profession! :-) |

How can a book about the birth of a new computer possibly be of

interest to somebody who is not a computer freak? Well, this book

is about passion. Not the passion between a man and a woman, but

rather the passion that some men have for their work. Its subject

is the people who design and build computers, not the computer

itself.

How can a book about the birth of a new computer possibly be of

interest to somebody who is not a computer freak? Well, this book

is about passion. Not the passion between a man and a woman, but

rather the passion that some men have for their work. Its subject

is the people who design and build computers, not the computer

itself.