|

The audacity of the Apollo project

|

|

|

President John F. Kennedy's announcement May 25, 1961 before a joint session of Congress . |

|

Click

image for 11-sec video clip.

|

Following the shock of the Soviet Union's Sputnik satellite in 1957, and the additional humiliations inflicted upon the U.S. in April 1961 - the Bay of Pigs fiasco and the first manned space flight by Yuri Gagarin - it came as no big surprise that the U.S. would try to surpass the Soviet achievements in space as soon as possible. What was surprising was the form and the timing of President Kennedy's response. On May 25th , 1961 he proposed to a joint session of congress that the U.S. "should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the Earth".

Even to those of us who understood something of what this challenge implied - and perhaps especially to us - the audacity of Kennedy's announcement was staggering. Just consider the following points:

- The only U.S. manned space flight, a brief sub-orbital hop on a tiny

Redstone rocket, had taken place just three weeks before Kennedy's speech.

- Although some Russian dogs had survived in space for a day, there

was no empirical evidence that humans could survive for a week in a

zero-g environment, let alone perform the demanding operations needed

for a lunar mission.

Would it be possible to absorb and digest food and drink? Would it be possible to sleep in free fall?? - Gagarin had experienced about 100 minutes of weightlessness during his flight; Shepard about 5 minutes.

Flights with airplanes in parabolic trajectories ("the vomit comet") offer about 20 seconds of microgravity.

- The cislunar radiation environment was a big question mark. The Van Allen belts had been discovered, but not mapped in detail. Solar particle radiation beyond the Van Allen belts was largely unknown, and in fact a rare solar flare event would have been a very serious health hazard, especially to astronauts in the Lunar Module and during excursions on the Moon's surface.

- The composition of the lunar surface was unknown. There was concern that a thick layer of dust might complicate landings and hamper operations.

- At the time of Kennedy's announcement, there was no compelling scenario for the lunar landing mission. The leading hypothesis was that a single gigantic booster rocket, the Nova vehicle, would propel a landing vehicle to the Moon. The return would be directly to the Earth. An alternate scenario was that two or more heavy carrier rockets would deliver payloads into Earth orbit, where the lunar vehicle would be assembled or fuelled. Again, the return would be direct-to-Earth. Other possibilities were lunar surface rendezvous, i. e. to deliver cargo (fuel and/or an unmanned ascent vehicle) to the Moon which would be used for the return trip; or even in-transit rendezvous and re-fuelling during the trip to the Moon (a nerve-wracking scenario proposed in a paper at the IAF congress in Stockholm in 1960). - The concept of a mother ship orbiting the Moon, while a separate lander descended to and ascended from the lunar surface and then performed a rendezvous and docking with the mother vehicle, was hardly taken seriously at the time.

|

|

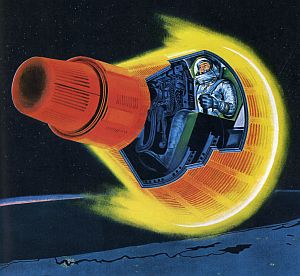

An early NASA artist's impression

of a Mercury spacecraft's re-entry into the Earth's atmosphere.

|

As a consequence, what rockets and spacecraft to design and build was very much an open question at this point. The feasibility of rendezvous and docking operations was unproven. The problem of space navigation was unsolved. (It turned out that - if memory serves - the returning Apollo capsule had to hit a 40-km wide corridor going into the atmosphere at the end of its 380,000 km return trip from the Moon. Coming in too low meant excessive g forces and incineration; going too high meant skipping out into space again, much as a flat stone thrown at a low angle to a water surface may skip the surface instead of penetrating it.) Computers were primitive by today's standards. ("We went to the Moon on 16 K.") Engineers still carried sliderules. And to top it off, this was in an age when a hefty share of rocket launches ended in spectacular explosions. Indeed the first attempt to orbit an unmanned Mercury capsule had failed just a month earlier, when the Atlas rocket had had to be destroyed by the safety officer.

My Canadian colleague Dr. David Goodenough used to say: "Out of the three constraints on a project: What is to be achieved? By when? How much can it cost?, I refuse to commit myself to more than two." Kennedy had followed this principle in his announcement, but contrary to prevailing beliefs, in practice there was a cost cap. NASA Administrator James Webb had committed to a budget of some 22 billion US dollars for the whole project. He had wisely included a huge margin in the figure he had presented to Kennedy, and in turn his managers had their own margins. For instance, Wernher von Braun made sure that his Saturn rockets had a lot more power than the original requirements stipulated, knowing from experience that initial weight budgets were bound to be exceeded. - As it turned out, the runout cost of the program was within budget, but in announcing the objective, Kennedy must have known that he was taking an enormous risk on the financial side as well.

Kennedy's aide and speech writer Ted Sorensen wrote: "The routine applause with which the Congress greeted this pledge struck him, he told me in the car going back to the White House, as something less than enthusiastic. Twenty billion dollars was a lot of money. The legislators knew a lot of better ways to spend it."

|

||

|

Unlike von Braun, Kennedy and Webb were no spaceflight romantics. There is no evidence that they were particularly impressed with the awesome fact, that after 4,000 million years of evolution, within our own short lifetime on this planet - a mere blink of the eye - mankind would break the bonds of gravity and travel to another celestial body. A transcript released just a few years ago shows that Kennedy tried to imprint the overriding importance of beating the Soviets to the Moon on Webb, while Webb tried to defend a "balanced program" with equal priority for unmanned planetary missions etc. - Surprisingly, Webb left NASA in October 1968, just on the eve of NASA's greatest achievements.

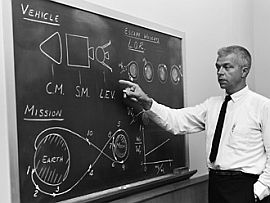

In July 1962, Kennedy made another courageous decision, when he endorsed NASA's proposal to adopt the Lunar Orbit Rendezvous approach for Apollo. This mode had originally been dismissed as an exotic, extremely risky scenario. It would greatly increase the number of milestone events during the mission that could go wrong, with disastrous consequences. But one farsighted engineer at the Langley Research Center, John Houbolt, gradually managed to convince top management that this mode was the most practical way - perhaps even the only one - to meet the deadline. The decision-making process makes for fascinating reading. The early favored scenario of a single launch of the huge Nova booster and a direct flight to the Moon's surface had to be discarded because of the time required to build and test the monster rocket. The scenario preferred by the Marshall Space Flight Center under von Braun, assembly and fuelling in low Earth orbit before departing on a direct flight to the Moon's surface, was considered more viable, but the design of the large moon lander turned out to be very tricky, with the crew residing high above the ground. Gradually, the numbers convinced von Braun that Lunar Orbit Rendezvous (LOR) was the way to go, and he showed great leadership in bringing his lieutenants over to the LOR camp.

But even with all the rationale provided by the engineers and their calculations, there still was a lot of uncertainty in assessing the risks involved in the different scenarios. The two orbital Mercury flights that had taken place at the time of the LOR decision demonstrated how hazardous spaceflight still was. During John Glenn's flight there had been an indication that the heat shield had come loose, and a high-risk decision had been made to attempt re-entry with the retro-rockets still attached to the heat shield, something that could have perturbed the air flow to a dangerous degree. Scott Carpenter's flight overshot the intended recovery area by some 400 km due to an off-nominal attitude of the spacecraft when the retro rockets were fired. And the previous summer, Grissom's sub-orbital flight had ended in the loss of his spacecraft after splashdown. Grissom himself had been half drowned. - Rendezvous and docking operations still lay in the future, and there still was no detailed information on the conditions on the lunar surface. The first Ranger closeup images were to be transmitted as late as 1964, and the first unmanned Surveyor lunar lander arrived in June 1966.

|

| Visiting a friend in Huntsville, Ala. in 1967. The F1 engine is in the center. Five F1s were clustered in the first stage of Saturn V. |

In 1962, there obviously was no experience of building and operating a rocket as large as the Saturn V, 110 m tall and weighing 3000 tons at launch, burning 13 tons of fuel per second. Just how reliable would it be? Major technical problems would have to be overcome, and were. As late as in August 1968, there were unacceptable longitudinal oscillations in the vehicle during launch ("pogo oscillations"), yet, remarkably, the problem was fixed and the Saturn V sent on a manned circum-lunar mission just four months later. - Earlier, the minor engineering problem of building the Vertical Assembly Building to accomodate the Saturn V, the world's largest building by volume at the time, had been solved. The building was designed to withstand hurricane force winds...

Above all, in the case of the LOR scenario, Kennedy had to face the very real possibility that American astronauts might be stranded in lunar orbit without any hope of rescue, facing a slow and very public death. And for months and years after that, every time someone looked at the moon, there would be the knowledge that the corpses were still circling up there.

Today, with the record of six successful landings on the Moon, and with no loss of life in space during all of the Mercury, Gemini, Apollo and Skylab programs, it is all too easy to overlook the many risks that were present, and the close calls that were averted, during that era. In addition to the tragic Apollo 1 fire, there was the accelerating spin of the docked Gemini-Agena vehicle with Armstrong and Scott in 1966; the dramatic explosion on Apollo 13 that nearly proved fatal (and would have been, had it occurred on Apollo 8); the wildly gyrating Lunar Module on Apollo 10; Apollo 12 struck by lightning during launch; and undoubtedly a large number of small problems that could have escalated but didn't.

The Apollo program was hugely successful, but there were no guarantees that this would turn out to be the case when Kennedy made his decision in 1961.

Further reading

1. Chariots

for Apollo: A History of Manned Lunar Spacecraft

2. Apollo

Lunar Surface Journal