|

The

Exploration of Space - Arthur C. Clarke

|

|||||||||||

|

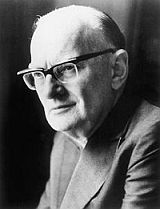

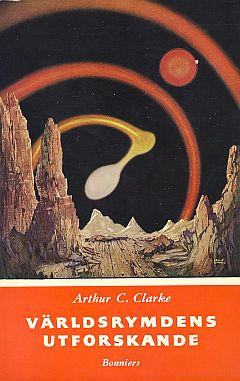

I had been introduced to the possibility of space travel as a child by my father, who had drawn V2 rockets for me in 1948 and predicted that men would walk on the Moon within thirty years. A few years later, I watched a reasonably realistic movie about a manned expedition to the Moon, George Pal's "Destination Moon", and was fascinated by Bonestell's magnificent paintings of imagined vistas of the Solar System. I had also read a short book on the physics of space travel by Otto Willi Gail. Still, human space flight seemed a distant goal; something that might be achieved sometime in the 21st century. In the early 1950s, I was not aware of any significant development in this direction. An altitude record of 400 km had been set in 1949 with a two-stage rocket: a V2 carrying a small WAC Corporal, but I realized that it had achieved only a small fraction of the speed needed to achieve earth orbit, and with a very small payload. — For several years, all further progress in rocketry was cloaked in military secrecy. When "The Exploration of Space" was translated into Swedish in 1954, it came as a revelation to me. I received it from its translator Sven Hallén, a journalist at Dagens Nyheter who was a friend of the family. — He also devoured science fiction books and handed them down to me, by the hundreds. By the way, he handed me Keyhoe's book on "Flying Saucers", which he had been asked to review, with an accompanying note from the editor at Dagens Nyheter: "This book seems completely deranged. I hope you will deal with it accordingly." — Here, for the first time, I could read a relatively detailed treatment, addressed at adults, of the prospects for space flight. The book was based on pre-war studies carried out by enthusiasts at the British Interplanetary Society, complemented with an account of German wartime accomplishments. The performance figures of the V2 rocket were known and could be extrapolated to larger designs. A 150-ton three-stage rocket based on V2 engines should be able to lift a payload of 50 kg into orbit. If engines could run on hydrogen and oxygen, a 30-ton rocket might achieve the same orbital payload. It should be possible to launch an artificial satellite within 10 years. (The book was originally published in 1951.)

Clarke takes us on a tour of all the basic aspects of spaceflight: the multi-stage rockets, trajectories and orbits, g forces and weightlessness, space suits, rendez-vous and docking, assembly of space stations and orbital refuelling of interplanetary spacecraft, possible applications of unmanned satellites, interplanetary robotic probes, manned bases on the Moon and on Mars. — He even touches on interstellar flight, concluding that it will remain out of reach for the foreseeble future, but — ever the optimist — considers that anything that does not contradict the fundamental laws of physics will ultimately be achievable. He has famously pointed out that "Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic". (How would Mozart or Chopin have reacted to an MP3 player?) Another famous Clarke observation is that when a distinguished elderly scientist claims that something is possible, he is almost certainly right, while when he claims that something is impossible, he is very probably wrong. Some of Clarke's predictions have proven to be remarkably accurate. He concludes that even a high-performance rocket with a single stage will only barely be able to reach orbital velocity. Today, almost 60 years later, "SSTO" (Single Stage to Orbit) still has not been realized. It would be technically possible to achieve, but it would be wasteful and pointless as long as a recoverable vehicle with a decent payload capacity remains out of reach.

The novel ends: Beyond the lagoon, past the friendly shelter of the coral reef, the first frail ship was sailing into the unknown perils and wonders of the open sea. — An apt description, I think, of what was to come in 1968, when Apollo 8 "slipped the surly bonds of earth..."! Shortly after Clarke published The Exploration of Space, Collier's Weekly magazine in U.S.A. printed a series of articles by Wernher von Braun. Von Braun's vision was ambitious and grandiose: he proposed a large wheel-formed space station with a 75 m diameter and a crew of 80 in a 2-hour polar orbit. The station would have important applications in Earth observation etc., but it would also serve as a springboard for fleets of spaceships going to the Moon and to Mars. During construction of the space station, 15 recoverable three-stage rockets, each with a launch mass of 6,400 tons, would deliver a 20-ton payload to the station every 16 hours! — The articles were lavishly illustrated with tantalizing drawings by Chesley Bonestell and other artists, showing amazing detail. They had a great impact on the American public, but I did not read them until 1958 when they came out in book form. I did see an animated "Man in Space" Disney film based on von Braun's vision sometime around 1955, but it was Arthur C. Clarke who convinced me that space flight was imminent.

"I'm not ashamed of the fact", he [Professor Maxton] said cheerfully, "that before Ray was born I was paying my college fees with the aid of my typewriter. Besides, someone had to write about space-travel before people would believe it was possible." — "But it didn't work out that way", objected Collins. "Most of those stories were so darn silly, and so badly written, that they had just the opposite effect. Everyone thought that interplanetary travel was stuff for the kids." — "So it was — in the 1940s", said Maxton. "They read about it — and when they grew up they made it happen." In March 1957, together with two classmates, I performed some experiments using standard fireworks rockets, where, to the consternation of many onlookers, we removed the pyrotechnics in order to improve performance. — By then, the development of ballistic missiles and plans for the International Geophysical Year had given some credibility to the proposition that artificial satellites would actually be launched within a year or so.

I joined the Swedish Interplanetary Society in the spring of 1957. It was housed in an old building at Malmskillnadsgatan in central Stockholm. It was the type of environment you might associate with an old-fashioned English club. Creaking stairs, narrow passages, antique furniture. A real fire trap. (The building was torn down just a few years later.) Here I quickly became the Society's Librarian; a great privilege, as it gave me instant access to the current issue of all the leading aeronautics and space journals along with the library's book collection. The Society held regular meetings, including lectures on various astronautical subjects: Orbital mechanics, rocket engines, space medicine etc. Its finest hour occurred in 1960, when it hosted a congress of the International Astronautical Federation in Stockholm. I served as an usher, carrying a ribbon in the Swedish colors, and met dignitaries such as Leonid Sedov, Hermann Oberth, Wernher von Braun and Theodore von Karman. — Or, come to think of it, perhaps its finest hour came the following year, when it organized a charter flight to the IAF Congress in Washington D. C. and the American Rocket Society's meeting in New York in October. That was my first flight across the Atlantic, a 14-hour flight to New York on a DC-7 with a stopover in Goose Bay, Labrador. Memorabilia and some details in Swedish here. But I digress. What I wanted to say was that it was Clarke's book that triggered my passion for spaceflight. Even before I graduated from high school, I had decided to become an engineer and to aim for a career in astronautics.

I went on to study engineering physics at the R. Institute of Technology in Stockholm. After graduation in 1963, I sought employment with von Brauns's team at NASA's Marshall Spaceflight Center. Despite an encouraging letter from him, and a follow-up letter, in the end it proved unrealistic to think that a fresh graduate from Sweden with no experience would be embraced by NASA. I was forced to follow the great adventure through trade journals such as Missiles and Rockets, Aviation Week (I still have a large collection from the 1960s in my garage) and Voice of America broadcasts from all the manned flights. (I have preserved my own tape recordings of VOA's coverage of Apollo 11.) — In 1966-67, I visited Stanford University on a European post-graduate scholarship, studying an assortment of space-related subjects. Then, after a few years at Saab Aircraft Co., I spent the rest of my professional life, 35 years, at Swedish Space Corporation and as a Swedish delegate at the European Space Agency. Strangely enough, Arthur C. Clarke's greatest achievement came in 1945, when he pointed out in Wireless World that satellites in geostationary orbit could provide the ideal solution for worldwide telecommunications. I say 'strangely', because on the one hand I find it surprising that such an obvious concept had not been proposed much earlier; on the other hand you would hardly expect an obscure 27-year old radar technician to make such a proposal and get it into print at that time. — Clarke used to lament (in jest), that he should have patented the idea. Fortunately, perhaps, his patent would have lapsed by the time the first geostationary satellite was launched. — More recently, some aerospace companies have tried to patent certain orbits useful for telecommunications — and trajectories around the moon useful for recovering satellites injected into the wrong orbit — opening up a vast (literally!) new arena for litigation.

Today, Clarke is best remembered as a science fiction writer, especially as the author behind Stanley Kubrick's hugely successful movie 2001: A Space Odyssey. What many people liked about Clarke's stories (including my father) was that they combined great inventiveness with solid, or at least plausible, science. He described the early stages of the space age in Prelude to Space, The Sands of Mars and A Fall of Moondust (an intriguing story, with lots of physics, about a rescue operation for a manned lunar surface vehicle which has disappeared into a pocket of dust). He speculated about mankind's first encounter with an alien civilization in The Sentinel (which was expanded into 2001; a transmitter has been left on the Moon by aliens who visited the Earth eons ago, to alert them that a spacefaring civilization has now arisen on our planet), in Childhood's End, and in Rendezvous with Rama, in which a huge alien starship (similar to an O'Neill space colony) passes through the solar system on a hyperbolic trajectory. In The Fountains of Paradise he proposed a "space elevator": a high-strength wire would connect the Earth's surface with a satellite at geostationary altitude 36,000 km above the equator, allowing a high-speed elevator to run up and down the wire, eliminating the need for wasteful rocketry. (This idea may not be as outlandish (no pun intended!) as it sounds. Its weakest point may be that the space elevator could become an attractive target for terrorist groups.) Although a Briton, Arthur C. Clarke lived the last 50 years or so of his life in Sri Lanka, where he enjoyed scuba diving and, understandably, became an early adopter of advancements in telecommunications technology. He was knighted in 2000. He enjoyed his fame and had a whole room in his home allotted to memorabilia from his remarkable career. Some additional web links

|

Arthur

C. Clarke died just a few weeks ago, in March 2008. Very few people

have had more influence on my life than he did, even though I talked

to him only once, nearly fifty years ago.

Arthur

C. Clarke died just a few weeks ago, in March 2008. Very few people

have had more influence on my life than he did, even though I talked

to him only once, nearly fifty years ago.

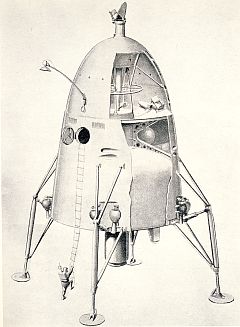

In

1947, Clarke wrote his first science fiction novel, Prelude to

Space. (Published only in 1951, it was dedicated to "Val

and Wernher, who are doing the things I merely dream about".)

It describes the first expedition to the Moon, in 1978, using a

two-stage vehicle with atomic rocket engines. "The old chemical

rockets would have needed several thousand tons of fuel to carry

a load of one ton to the Moon and back, which wasn't practicable."

(A fairly accurate figure: The Saturn V vehicle weighed

3,000 tons at liftoff, and soft-landed 7 tons on the Moon. The Command

Module weighed 5 tons at splashdown in the Pacific.) The

first stage is a ramjet-powered winged vehicle. The project is financed

by an international foundation headquartered in London (its

location is modestly described as an historical accident),

having its rocket range in the Australian desert. —

The cost figures are rather less prescient than the engineering

projections: Professor Maxton once calculated that the ship had

cost about ten million pounds in research and five millions in direct

construction.

In

1947, Clarke wrote his first science fiction novel, Prelude to

Space. (Published only in 1951, it was dedicated to "Val

and Wernher, who are doing the things I merely dream about".)

It describes the first expedition to the Moon, in 1978, using a

two-stage vehicle with atomic rocket engines. "The old chemical

rockets would have needed several thousand tons of fuel to carry

a load of one ton to the Moon and back, which wasn't practicable."

(A fairly accurate figure: The Saturn V vehicle weighed

3,000 tons at liftoff, and soft-landed 7 tons on the Moon. The Command

Module weighed 5 tons at splashdown in the Pacific.) The

first stage is a ramjet-powered winged vehicle. The project is financed

by an international foundation headquartered in London (its

location is modestly described as an historical accident),

having its rocket range in the Australian desert. —

The cost figures are rather less prescient than the engineering

projections: Professor Maxton once calculated that the ship had

cost about ten million pounds in research and five millions in direct

construction. My

faith in Clarke earned me a taste of martyrdom. For years, I decorated

my room with a picture showing the first orbit of a satellite launched

from Florida. In the mid-1950s, space flight was not taken seriously

by very many people in Sweden, and a teacher called me "the

little man from the Moon". Besides, Clarke himself was best

known as a science fiction writer. In Prelude to Space he

mischievously writes:

My

faith in Clarke earned me a taste of martyrdom. For years, I decorated

my room with a picture showing the first orbit of a satellite launched

from Florida. In the mid-1950s, space flight was not taken seriously

by very many people in Sweden, and a teacher called me "the

little man from the Moon". Besides, Clarke himself was best

known as a science fiction writer. In Prelude to Space he

mischievously writes:

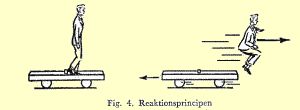

My

father encouraged me and borrowed Hermann Oberth's "Wege

zur Raumschiffahrt", published in 1929, from the Library

of the R. Institute of Technology. It contained a lot of technical

information that I absorbed like a sponge. (My math education had

by then reached the calculus.) Amusingly, the technical stuff was

punctuated with diatribes against critics who claimed that a rocket

could not function in a vacuum as there was nothing "to push

against"! One would think that a thought experiment, such as

this one from Clarke's book, should make it intuitively obvious

that an atmosphere is not needed to make a rocket work. (On

the other hand, intuition cannot always be trusted. Just consider

My

father encouraged me and borrowed Hermann Oberth's "Wege

zur Raumschiffahrt", published in 1929, from the Library

of the R. Institute of Technology. It contained a lot of technical

information that I absorbed like a sponge. (My math education had

by then reached the calculus.) Amusingly, the technical stuff was

punctuated with diatribes against critics who claimed that a rocket

could not function in a vacuum as there was nothing "to push

against"! One would think that a thought experiment, such as

this one from Clarke's book, should make it intuitively obvious

that an atmosphere is not needed to make a rocket work. (On

the other hand, intuition cannot always be trusted. Just consider